Genome annotation#

A vast sea of a,c,g,ts#

By early 2000s, the first draft of the human genome sequence was publicly available. We had a blueprint, but it seemed like a vast sea of a,c,g,t mumbo jumbo. To decode the blueprint, genes and other functional elements had to be located in the sequence. We call this process genome annotation. Given the sheer size of the human genome sequence, annotating it would be a tall task; and this made many biologists and bioinformaticians alike very happy, as it meant they had a job for the rest of their lives.

With the objective to annotate the human genome, a large science consortium named ENCODE was organized in 2003. Relying mainly on experimental techniques but also on computer algorithms, the first phase (2003-2007) of the project was able to annotate the protein-coding regions. Here’s the front cover of the Nature issue reporting this work.

Fig. 18 Front cover of Nature Vol 447 Issue 7146, 14 June 2007.

Source: https://www.nature.com/nature/volumes/447/issues/7146#

However, this annotation accounted for only ~1% of the genome, the protein-coding part. The project was expanded to cover the whole genome; and in 2011-2012, it was reported that ~80% of the genome had been annotated ([ENCODE Project Consortium, 2011],[ENCODE Project Consortium, 2012]). There were further expansions to the ENCODE project; and with discoveries of new functional elements like the many varieties of non-coding RNAs, the task of genome annotation continues to this day.

Now say you have your own favorite organism, and you sequenced and assembled its genome. These days, even labs with moderate resources are able to afford sequencing, so this is not a remote possibility. But what if you don’t have the resources like that of the ENCODE project to run a variety of assays to annotate the genome? Can we do it just using computer algorithms? With good quality reference databases, we might be able to. And that is what we will look at in this module.

The annotation problem#

Before looking at the annotation techniques, let’s discuss the problem a bit.

The annotation problem takes a DNA sequence as input and applies labels to each nucleotide.

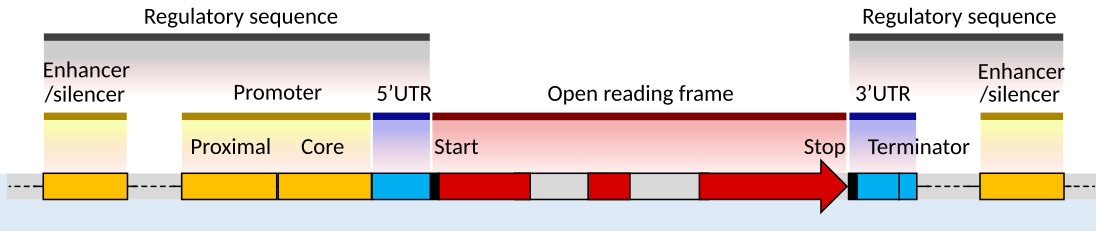

Take for example the problem of gene finding. Recall the structure of a typical eukaryotic gene.

Fig. 19 Source: Image cropped from https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Gene_structure_eukaryote_2_annotated.svg#

Given a sequence like the one below, and assuming no alternative splicing, we might want to label the nucleotides like so:

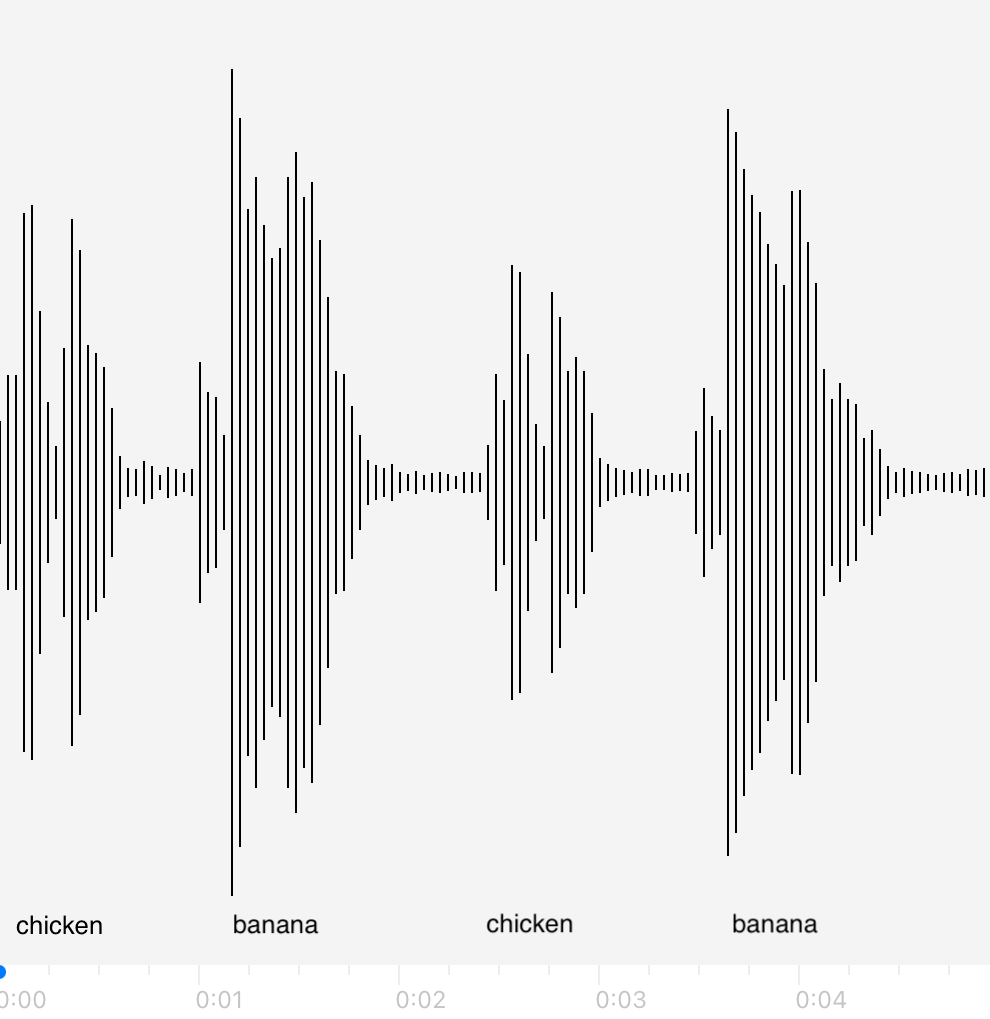

This kind of labeling problem is not new, similar versions of it have arisen in other domains. In audio signal processing, the task of speech recognition is to label intervals of raw audio signals by words.

In natural language processing, the problem of parts-of-speech tagging is to label words of a sentence by what part of speech (verb, noun, adjective) it is, or the problem of named entity recognition is to label words in a document by entries in a set of predefined categories (e.g. person, place, movie). Here’s an example of POS tagging.

Sasagot |

ang |

mga |

estudyante |

ng |

pagsasanay |

bukas. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

verb |

subject marker |

plural modifier |

subject |

object marker |

object |

adverb |

Labeling is a bit easier with languages that have separation between words. DNA sequences don’t have “words”. So in some it is closer to POS tagging of languages like Japanese which do not use spaces. Here’s a valid Japanese sentence written in Hiragana. Try parsing it if you know the language !

うちにはにはにはにはにはにはとりがいる。

The approaches#

By comparing against already annotated sequences#

One approach is to take reference sequence(s) that are already well annotated, and find (sub-)sequences in the reference that are similar to (parts of) the input sequence. One way to find and measure sequence similarity is using sequence alignment, in which nucleotides of the query are aligned to those of the reference. We will discuss sequence alignment in greater detail in the next module. Based on the alignment(s) found, annotations on the reference are copied onto the query.

References#

ENCODE Project Consortium. A user's guide to the encyclopedia of DNA elements (ENCODE). PLoS Biol., 9(4):e1001046, April 2011.

ENCODE Project Consortium. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature, 489(7414):57–74, September 2012.