Modeling a family of sequences by a profile hidden Markov model#

Earlier we saw that a profile can represent a multiple sequence alignment of a group of sequences. We now look at a more sophisticated way to model a group of sequences. It marries the idea of a profile with a hidden Markov model, and unsurprisingly is called a profile HMM or pHMM.

A pHMM is especially handy when we need to decide if a query sequence is a member of a certain family or not. This problem is encountered quite often, and there are databases that maintain pHMM models of protein families, transposable elements, viral proteins.

Why not just pairwise alignment#

Why not just align the query to each member of the group ? First, there would be quite a lot of pairwise alignments to deal with. But more importantly, we’d be missing position-specific information that helps in finding more accurate alignments. For example, the 18th column in the MSA in the previous section seems to be highly conserved, so we know to penalize a mismatch in this column more strictly. This kind of group information allows pHMMs to be more sensitive than pairwise alignments in identifying remote homologs.

Profile HMM#

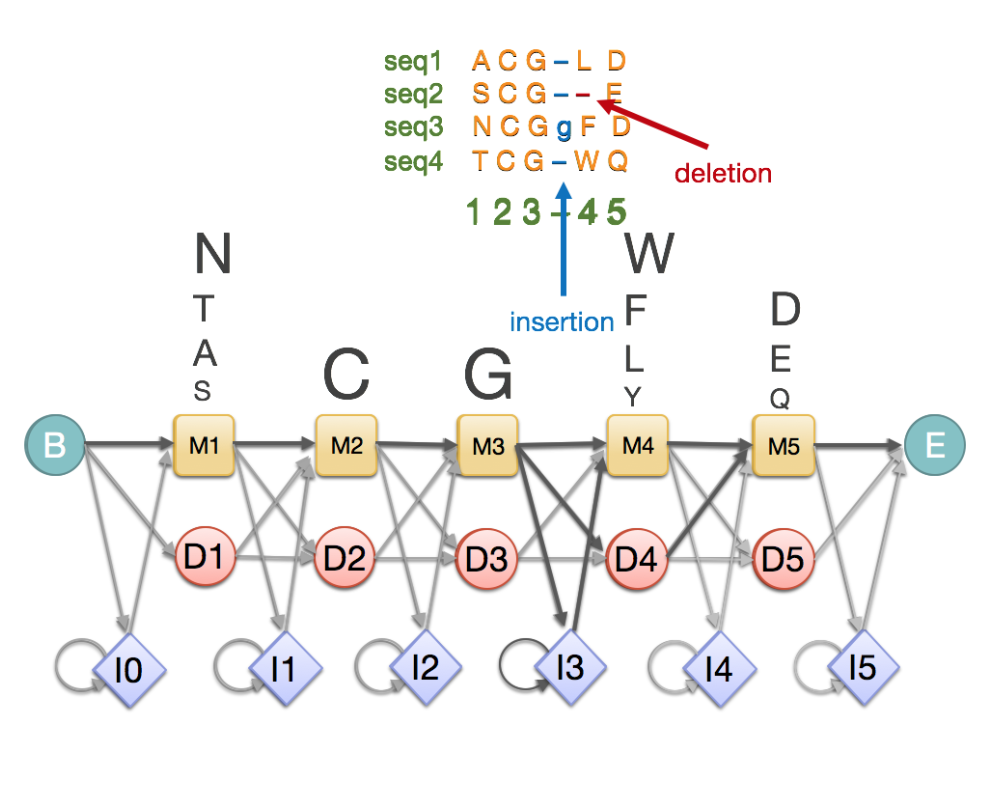

A profile hidden Markov model (pHMM) is special kind of HMM that models a family of sequences. It is typically built from an MSA and captures position specific information that you might otherwise see in an MSA. Here is a toy example:

Fig. 39 A toy example of a profile HMM showing its correspondence to an MSA.

Source: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/training/online/courses/pfam-creating-protein-families/what-are-profile-hidden-markov-models-hmms/#

As you can see, a pHMM has a left-to-right structure with no cycles, and has repetitions of triplets of match states (\(M\)), insertion states (\(I\)), and deletion states (\(D\)). The \(M\) and \(I\) states emit amino acid \(a\) (or nucleotides for DNA profile HMM) with some emission probabilities. The \(D\) states are silent.

Building a pHMM from a multiple sequence alignment#

It is typical to build a pHMM from a given MSA (although in theory we could build one without MSA and instead use a pHMM to compute an MSA).

A simple approach is to estimate the pHMM parameters is to represent by match states the columns of the MSA that have more residues than gap characters, and by insertion states columns that have more gaps than residues. This decides the number of triplet (M,I,D) blocks there will be in the pHMM thus deciding the model architecture.

Next, the transition probabilities can be estimated by counting the number of each transition made by the sequences in the MSA when their paths are traced on the pHMM.

The emission probabilities of the match and insert states can be similarly estimated from the sequences in the MSA.

Here’s a video describing the process with a toy example.

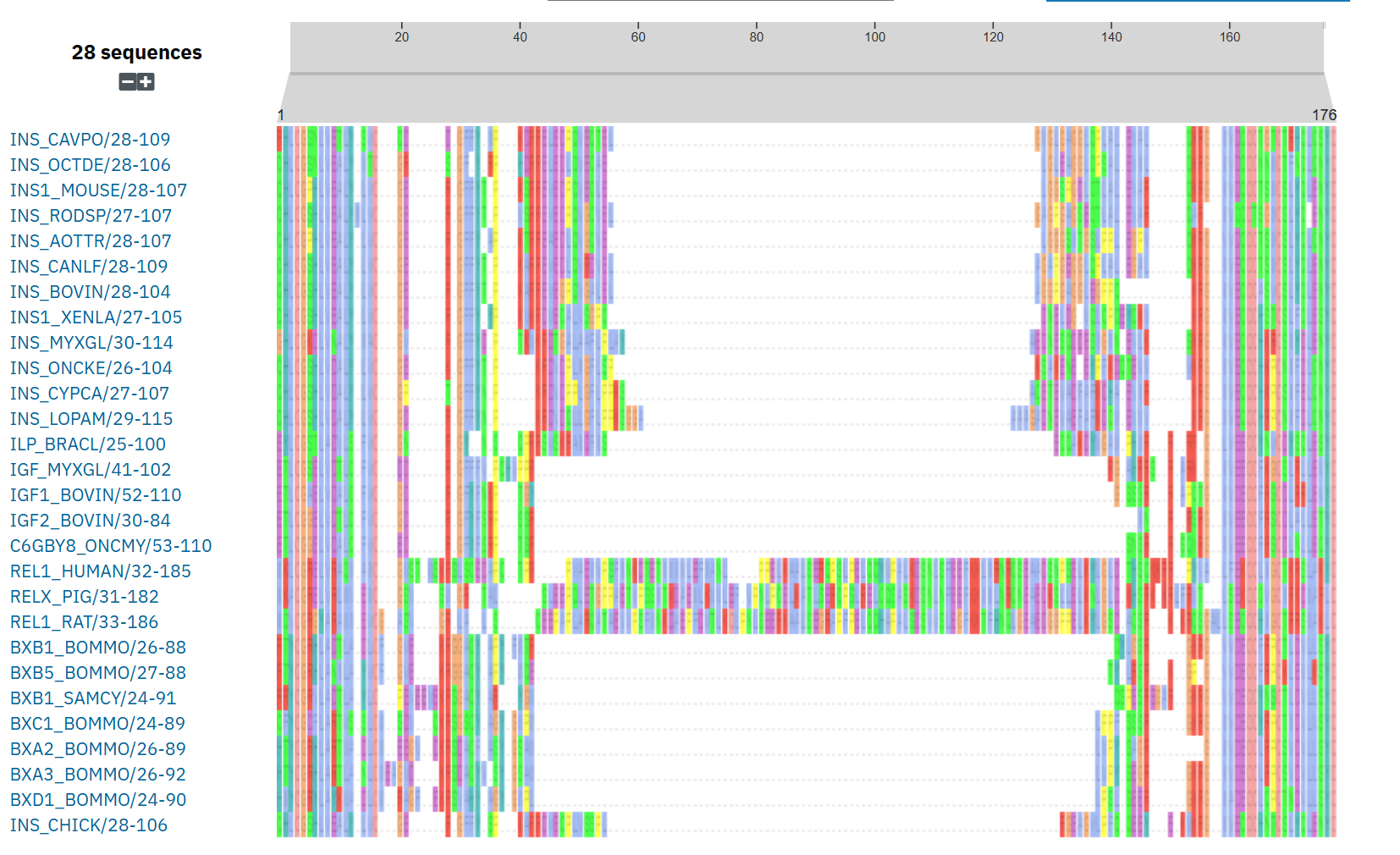

Here’s an actual example from PFAM. Shown below is the MSA of members of the Insulin/IGF/Relaxin family.

Fig. 40 An MSA of Insulin/IGF/Relaxin family from PFAM/InterPro.

Source: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/entry/pfam/PF00049/entry_alignments/?type=seed#

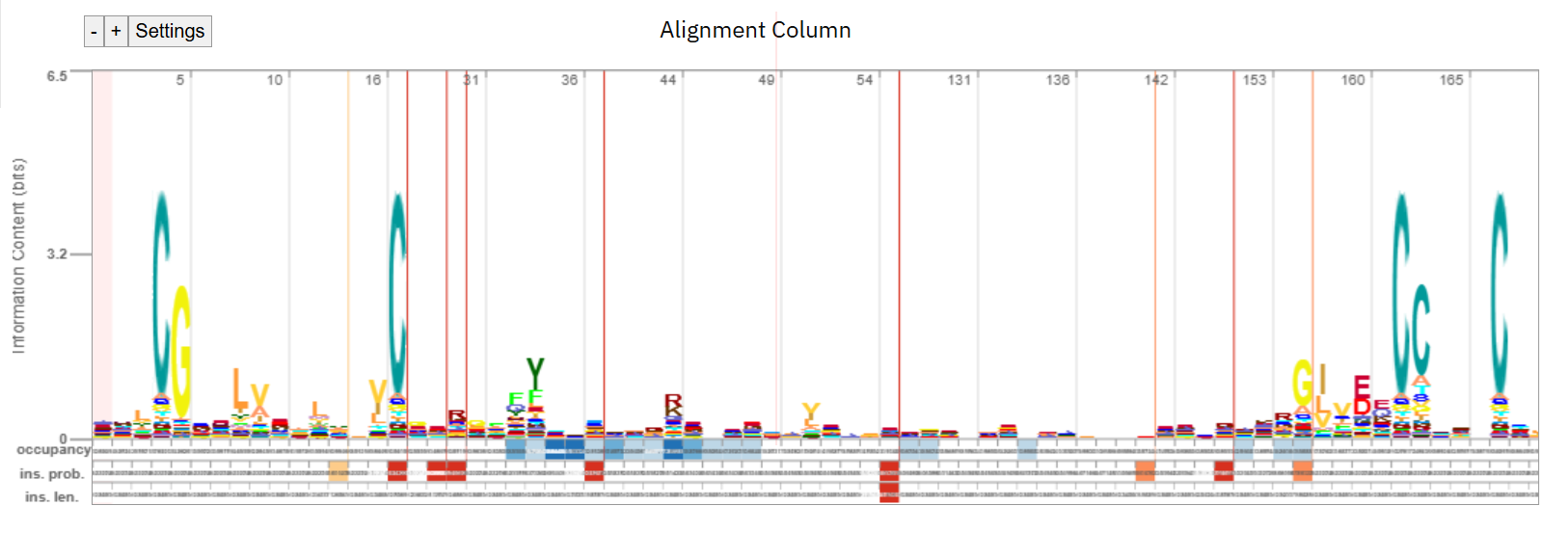

Shown below is a “logo” representation representation of the pHMM.

Fig. 41 A profile of Insulin/IGF/Relaxin family from PFAM/InterPro.

Source: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/entry/pfam/PF00049/entry_alignments/?type=seed#

Aligning a query to a pHMM#

Viterbi path#

An alignment \(A\) of a query sequence \(X\) to a pHMM is a path (sequence of state sequences) through the pHMM. An alignment \(A^*\) that maximizes the joint probability \(p(X,A^*|pHMM)\) is called a Viterbi path. In our earlier foray into HMM, we discussed the Viterbi algorithm that computes \(A^*\) and its probability .

Full probability#

The probability of \(A^*\), although highest, can still be very small, since the space of alignments is large and typically there are going to be many alignments very similar to \(A^*\) with almost the same probability.

The full probability \(p(X|pHMM)\) sums the probabilities of all alignments, and is often better than estimating a single uncertain alignment.

As discussed earlier, this can be computed by the forward algorithm.

These probabilities can be used to test for the hypothesis of membership against a suitable null model.

Posterior decoding#

Additionally, we can use the forward-backward algorithm to compute the probability that the \(i\)-th residue aligns to, say, a match state \(M_j\). This probability considers all possible alignments.

References#

Byung-Jun Yoon: Hidden Markov Models and their Applications in Biological Sequence Analysis, Current Genomics 2009, 10 402-415.

https://www.ebi.ac.uk/training/online/courses/pfam-creating-protein-families/

https://ics.uci.edu/~xhx/courses/references/krogh_anintroduction.pdf