What is bioinformatics, and why is it important?#

What’s in a name?#

There are differing opinions on what makes up the field of bioinformatics, what with similarly named overlapping fields like computational biology, mathematical biology, systems biology, population genetics, molecular evolution, etc. In an all encompassing, broad sweep, we can think of bioinformatics as the application of computational sciences (computer science, statistics, machine learning, mathematics, etc.) to problems in biology. Both these areas are evolving so fast, it’s futile to fixate on the exact defintion of bioinformatics.

Let’s instead look at how we have arrived at this point in time where modern biology and computational sciences go hand in hand.

Why bioinformatics?#

The art of seeing#

First, let’s go back in time to somewhere around the 17th century. The state of biology back then is described by the award winning writer, scientist, doctor Siddhartha Mukherjee, in his book The Song of the Cell as:

[Cell biology] was simply the art of seeing: the world measured, observed, and dissected by the eye.”

Indeed, curious folks like Robert Hooke and von Leeuwenhoek were busy peering into the lens of their fancy toy, the microscope. Here’s the one that Robert Hooke used.

Fig. 1 Microscope that Robert Hooke used (?)

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Hooke#/media/File:Hooke-microscope.png#

And were they seeing some really cool stuff !

Just by looking, they were able to discover cells and a lot about the morphology of cells.

Even until the early 20th century, microscopes – more sophisticated ones, of course – were still the mainstay of important biological discoveries. For example, David von Hansemann and Theodor Boveri observed dividing cancer cells in their microscopes, leading to the idea that cancers are a consequence of chromosomal abnormalities.

The new lens#

Fast-forward back to present day. Scientists today have access to more powerful ‘’lenses’’ like electron microscopy, mass spectrometry, and so on. But one technology that has propelled computer science directly to the center stage of biology is the sequencing technology.

A sequencer, to describe simply, is a machine that takes in a fragments of DNA molecules and produces the sequence of bases (a,c,g,t) in that molecule.

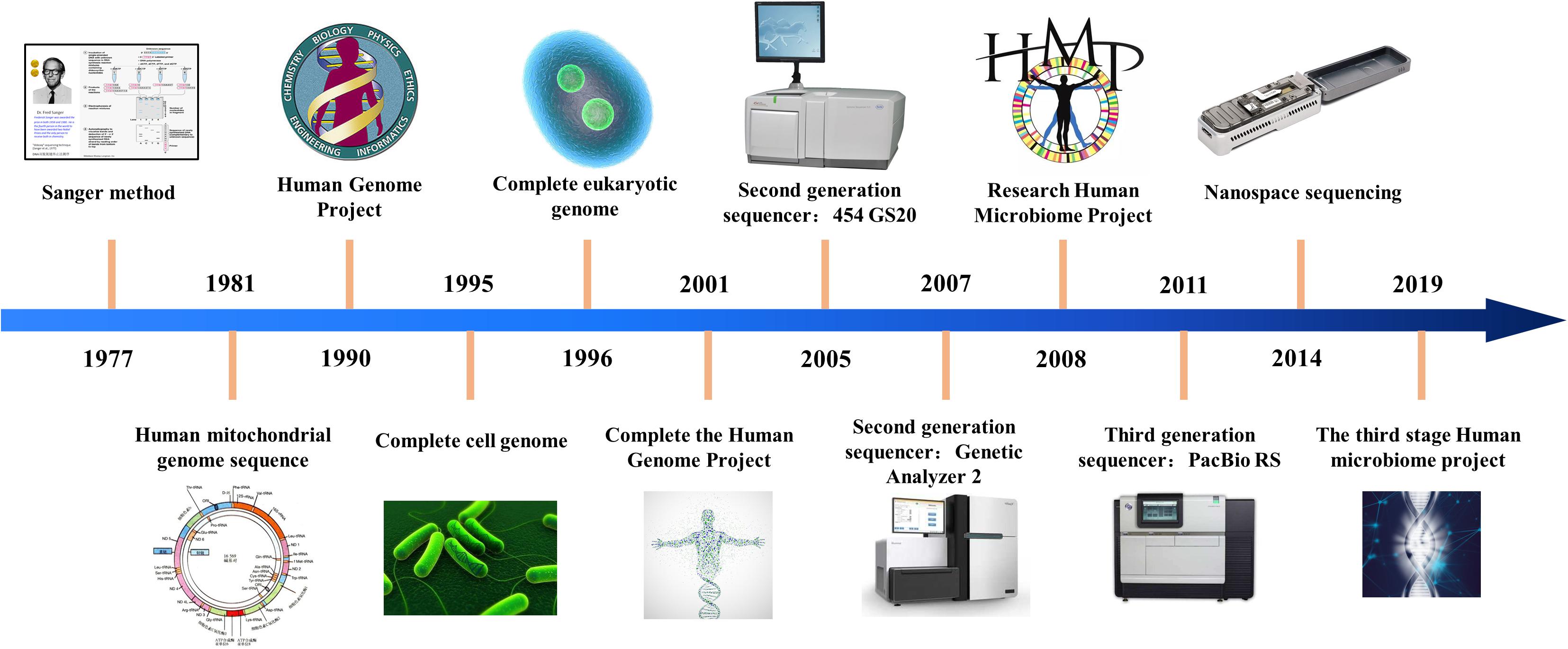

There are two interesting things about the history of sequencing technology. The first is the rapid pace of development, especially in the last two decades or so. One of the earliest versions of sequencers was developed by Frederick Sanger and colleagues back in 1977 (leftmost point in the image below), and this technology was the mainstay of major projects, e.g. the human genome project which published a draft version of the human genome sequence in 2001. However, Sanger sequencing is very slow and expensive, and not really suited to sequence big genomes. Sometime around mid-late 2000s, we started seeing sequencer with dramatically higher throughput. With prices coming down, this has resulted in a rush of sequence-your-favorite-organism projects, all over the world.

Fig. 2 History of sequencing technology Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/DNA_sequencing#/media/File:History_of_sequencing_technology.jpg#

The second interesting thing is the versatility of this technology. Although the biochemistry of sequencers are only good to read DNA, clever people have come up with ways to utilize sequencers to measure all sorts of biological stuff.

To see, we need to more than look#

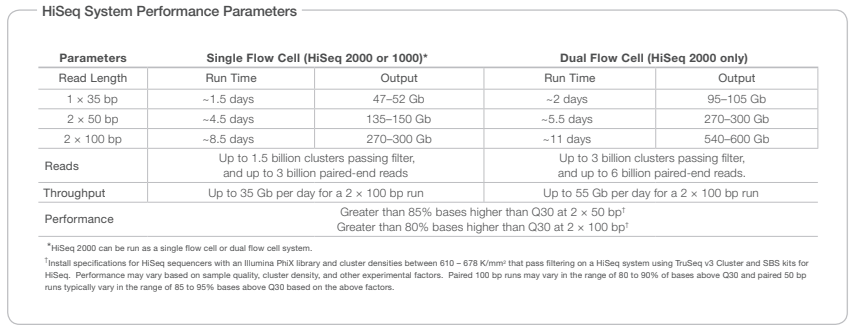

Each run of modern-day sequencer can produce tons of sequence data. To get a feel for this, consider Fig. 3 which is taken from the specification sheet of Illumina’s HiSeq sequencer. You can see that depending on how the sequencer is run, the output can amount to several tens to hundreds of Giga-bases (a base is one character in a DNA sequence, as we will learn later.)

Fig. 3 HiSeq specification Source: https://www.illumina.com/content/dam/illumina-support/documents/products/datasheets/datasheet_hiseq_systems.pdf#

Imagine using a sequencer like this, for say identifying mutations that might be involved in the initiation of acute myeloid leukemia. To do so, you might need to sequence tumor and normal genomes from a patient. To ensure generalizability of your observation, you might want to collect samples from multiple patients. When the sequencing is done and you look at the raw dataset, you will be facing a whopping several hundreds of Gigabytes of text data, even when compressed. Or, let’s say you are interested in epidemiology of a pathogen, say HIV/AIDS or SARS-Cov-2/Covid or TB. Compared to mammalian genomes, bacterial and viral genomes are smaller by many, many orders, but then you will likely want to sample hundreds of patients to be able to establish some phylodynamic patterns. Again, you are looking at several tens of Gigabytes of text data.

So how do we go from mountains of sequence data to insights into biological questions and hypotheses. It really depends on the question at hand, but it general, you will first need efficient tools to process the sequence data into some form that can be fed into statistical/machine-learning/artificial intelligence (what’s the difference anyway?) model, and then use those models to find patterns, make prediction, draw inferences, etc.

Being able to do this requires knowledge of data-structures, algorithms, statistics, machine learning, what we collectively call bioinformatics.

And, oh, the sights we have seen !#

Thanks to sequence bioinformatic methods applies to tons of data, we have a super high resolution view of biological systems. Here are just a few of the incredible things we have been able to do in the past decade or so:

Track and combat the SARS-Cov-2 pandemic [Attwood et al., 2022]

Catalog and characterize genetic mutations in cancers [Cornish et al., 2024]

Identify genes and genetic variations associated with important traits in crops[Wing et al., 2018]

Trace our own ancestry and history[Hellenthal et al., 2014, Wang et al., 2021]

Better understand our own genomes [ENCODE Project Consortium, 2012]

Characterize microbiome and connect them to health and diseases [Hou et al., 2022]

Further reading#

[Hagen, 2000] and [Gauthier et al., 2019] are two longer accounts of the history of bioinformatics.

References#

Stephen W Attwood, Sarah C Hill, David M Aanensen, Thomas R Connor, and Oliver G Pybus. Phylogenetic and phylodynamic approaches to understanding and combating the early SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Nat. Rev. Genet., 23(9):547–562, September 2022.

Alex J Cornish, Andreas J Gruber, and Ben et al. Kinnersley. The genomic landscape of 2,023 colorectal cancers. Nature, 633(8028):127–136, September 2024.

Jeff Gauthier, Antony T Vincent, Steve J Charette, and Nicolas Derome. A brief history of bioinformatics. Brief. Bioinform., 20(6):1981–1996, November 2019.

J B Hagen. The origins of bioinformatics. Nat. Rev. Genet., 1(3):231–236, December 2000.

Garrett Hellenthal, George B J Busby, Gavin Band, James F Wilson, Cristian Capelli, Daniel Falush, and Simon Myers. A genetic atlas of human admixture history. Science, 343(6172):747–751, February 2014.

Kaijian Hou, Zhuo-Xun Wu, Xuan-Yu Chen, Jing-Quan Wang, Dongya Zhang, Chuanxing Xiao, Dan Zhu, Jagadish B Koya, Liuya Wei, Jilin Li, and Zhe-Sheng Chen. Microbiota in health and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther., 7(1):135, April 2022.

Chuan-Chao Wang, Hui-Yuan Yeh, Alexander N Popov, and Zhang et al. Genomic insights into the formation of human populations in east asia. Nature, 591(7850):413–419, March 2021.

Rod A Wing, Michael D Purugganan, and Qifa Zhang. The rice genome revolution: from an ancient grain to green super rice. Nat. Rev. Genet., 19(8):505–517, August 2018.

ENCODE Project Consortium. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature, 489(7414):57–74, September 2012.