Exploring our own genomes#

We will now turn our attention to genomes, which just means all DNA in a cell. Given that genomes are “blueprints”, there are going to be differences among species and even among individuals of the same species. We can’t possibly go through all genomes, so to start out with, let’s just look at arguably the most interesting genome: our own.

In a human cell, DNA is packaged tightly into chromosomes which are found inside a nucleus. There is also some small amount of DNA in the mitochondria (yes, the powerhouse of the cell :D), but let us ignore the mitochondrial genome for now. Ignoring also the 3D structure of the chromosome, we can think of each chromosome as a string over the alphabet {a,c,g,t}.

There are so many questions we can ask about this sequence:

How are genes and other elements organized along the genome?

Is there any pattern in the sequence composition ?

How does the genome differ among different populations ?

How does our genome compare to that of say a chimpanzee or a mouse?

Some of these questions we will investigate in this module, some in later modules.

The reference human genome sequence#

There is one publicly available human genome sequence called the GRCh38 assembly (assembly because sequencing machines can only read fragments of DNA, and these fragments need to be assembled to reconstruct the whole genome sequence). This sequence is also called the reference human genome sequence, since it is widely used by researchers as a basis for comparing sequences produced by their own studies.

There is a long – and quite dramatic – history to how this reference genome came about. The most notable event in this history happened in March 2000, when the then US President Bill Clinton, announced the completion of the first draft of the human genome.

The first draft was not really complete since there were vast gaps of underdetermined sequence, and they are being patched up to this day ([Nurk et al., 2022]). Nonetheless, it was an exciting start, more so because it was also announced that the raw sequences would be released to the public domain (although one of the accompanying papers in Science remains behind a paywall (boo!)).

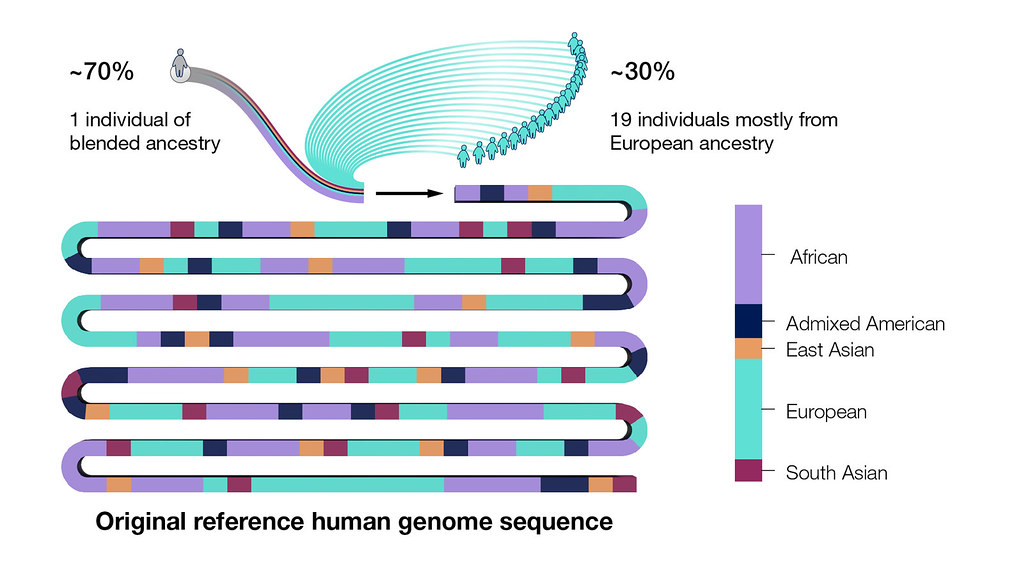

Many are now complanining about the lack of “reference-y-ness” of that sequence since it was obtained from the genomes of multiple individuals, mostly from North America and with European ancestry. It is not really representative of the global human population. These complaints are not unwarranted; but for this course though, it will serve as a wonderful dataset to explore. If you are a normal human being, your genome sequence is going to be very, very, very close to this sequence anyway.

Fig. 14 Whose genome was sequenced?

Courtesy: National Human Genome Research Institute.

Source: https://www.genome.gov/about-genomics/educational-resources/fact-sheets/human-genome-project#

Zooming in#

The GRCh38 assembly contains sequence from all chromosomes, which if you concatenate would result in a string ~3 Gigabases long. That’s a loooong sequence of just a,c,g,ts, and nothing will come out of by just eyeballing it.

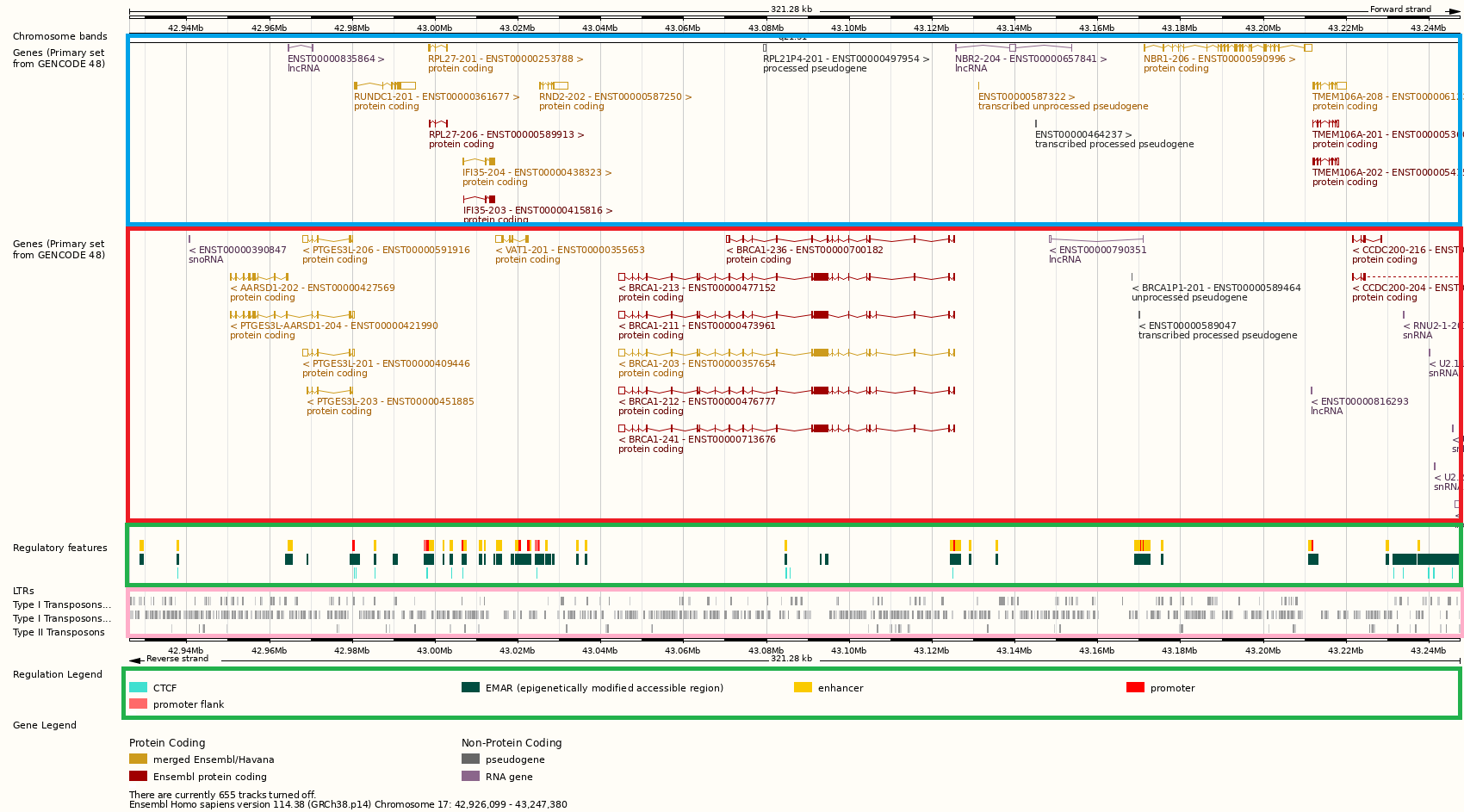

Let’s instead zoom in to one region in this sequence. The snapshot below taken using the Ensembl Genome Browser is of the neighborhood of Chromosome 17 position 43.10 Mb. The image is quite detailed, so you might want to open it up on a separate browser window. Let’s go through some of the elements we find in this region.

Fig. 15 Ensembl Genome Browser snapshot of the region around Chromosome 17 position 43.10 Mb of the Human GRCh38 assembly#

Protein-coding genes#

Inside the blue (red) box are genes in the forward (reverse) strand. Perhaps, the most notable of the genes is BRCA1 of the Angelina Jolie fame. BRCA1 is a DNA damage repair gene, whose mutant allele is associated with an increased risk of breast cancer. Hence the name.

Overall, there are ~20,000 protein-coding genes in the human genome.

Transcript variants#

The browser also shows splice variants of each gene. For example, 6 variants of BRCA1 transcripts are shown, although many more are known. You can see that each transcript has short exons (shown as boxes or almost vertical lines when the width is small) and long introns (shown as horizotal lines with a slight dip connecting two exons). This is generally true for any gene, and to the point where the exons of protein-coding genes only account for ~1% of our entire genome.

Noncoding RNA (ncRNA) genes#

Apart from the protein-coding genes, we can also see inside the blue and red boxes, non-coding RNA genes of several types: lncRNA, snoRNA, snRNA. These are genes which produce transcripts that are not translated but have regulatory or other functions.

The discovery of the vast diversity of ncRNAs is a recent development. We have known about two types of ncRNAs, ribosomal RNA (rRNA) and transfer RNA (tRNA), since the 1950s. The 2001 Nature paper accompanying the announcement of the first draft of the human genome said the following about ncRNAs.

‘’… it is important to remember that thousands of human genes produce noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) as their ultimate product …”

Thousands was a massive understimate, and there were indications that improved algorithms and screening techniques would bring that number up[Eddy, 2001] substantially. And then around 2008, with the invention of RNA-seq, a technique that allows high-throughput sequencers to sequence all RNA molecules present in the sample, we began discovering even more ncRNAs. Today the number of noncoding RNA genes stands at more than 40,000.

There is a bewildering variety of ncRNAs, and classification and nomenclature has been challenging. Often they are classified by length with an somewhat arbitrary threshold of about 200bp and have similar sounding names. Here’s just a few of the different kinds of known ncRNAs:

Short ncRNA (< 200 nt)

microRNAs (miRNA)

small nuclear RNA (sRNA)

small nuleolar RNA (snoRNA)

short interfering RNA (siRNA)

small Cajal body-specific RNA (scaRNA)

PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs)

Long ncRNA (lncRNA)

intergenic long RNAs (lincRNAs)

intronic lncRNA

sense lncRNA

anti-sense lncRNA

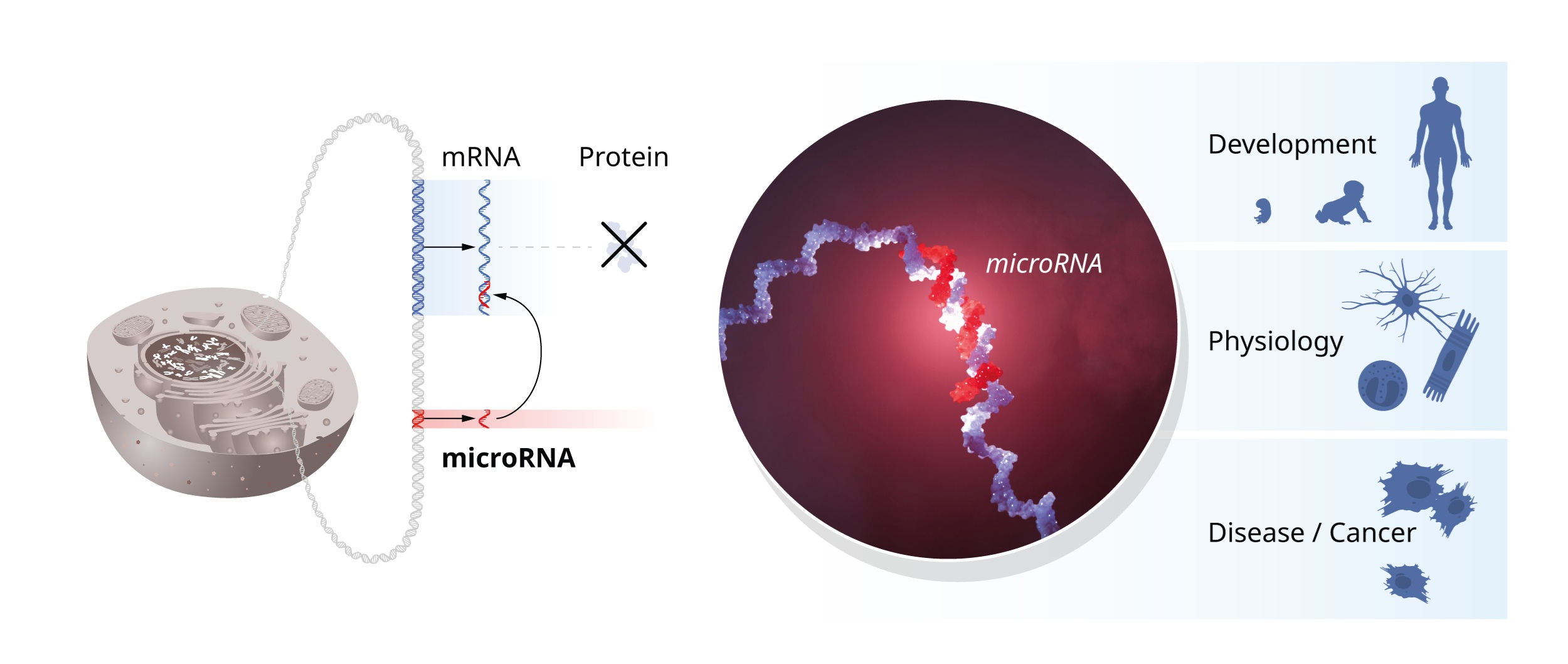

As a side note, Vicor Ambros and Gary Ruvkun were awared the 2024 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicinefor discovering microRNA and its role in post-transcriptional gene regulation. Here is an infographic from the press release:

Fig. 16 Source: Press release of 2024 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine award

Original title: “The seminal discovery of microRNAs was unexpected and revealed a new dimension of gene regulation.”#

Regulatory elements#

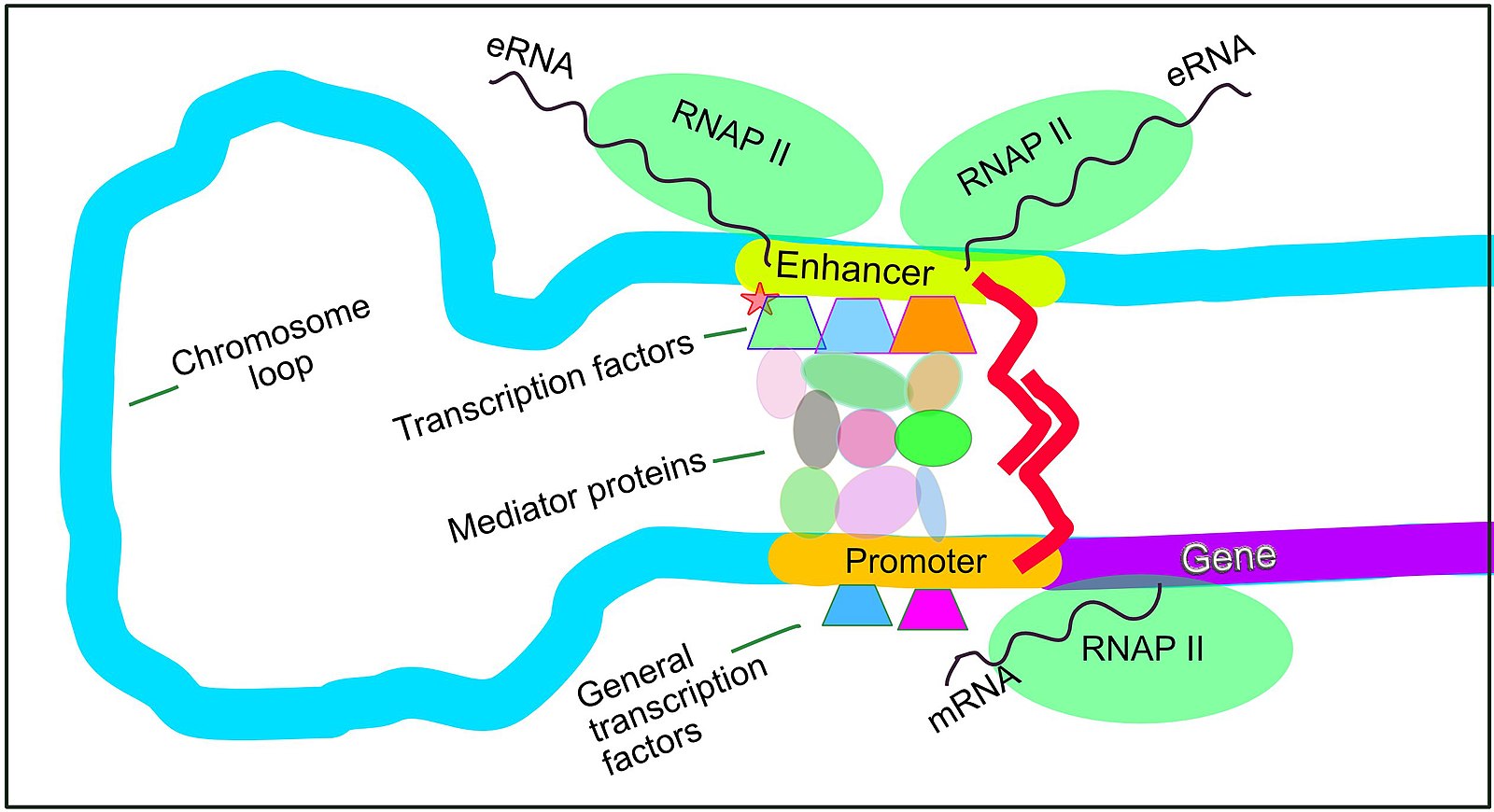

The green boxes contain information about regulatory elements, which play a role in the initiation or efficiency of transcription or translation. Fig. 17 shows our current understanding of transcription is regulated in mammals.

Fig. 17 Mammalian transcription regulation. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Regulation_of_transcription_in_mammals.jpg#

A promoter is defined loosely as a sequence upstream of the transcription start site which is important in transcription initiation. This site is where DNA-binding proteins (a.k.a. general transcription factors) and RNA polymerase assemble before the actual transcription begins. In the case of human protein-coding genes, which are transcribed by RNA polymerase II, the promoter sequence is typically upstream of the transcription start site and have some sequence signatures. One element of the promoter is a TATA box, so called because its sequence signature in regex looks something like \({\tt TATA[AT]AA[AG]}\).

An enchacer is like a promoter in that other transcription factors bind to this region and influence transcription of one or more genes. It can be distant from the gene whose expression it is controlling, and one enhancer can regulate multiple genes.

The genome browser snapshot also shows putative binding sites for CTCF which is a kind of transcription factor.

Pseudogenes#

Also in the blue and red boxes are psuedogenes. A pseudogene is a defective copy of a gene, and hence the name. The current release (version 48) GENCODE has cataloged more than 14000 pseudogenes.

They are classified based on how they came to be. A processed pseudogene is created when an mRNA get reverse transcribed and integrated into the genome. An unprocessed pseudogene arises from segmental duplication of an existing gene.

See here for more details on these interesting elements. More here [Cheetham et al., 2020]

Transposable elements#

The pink box shows transposable elements or transposons, which are mobile DNA that are/were sequences capable of moving about or replicating within the human genome. They can be anywhere from ~100bp to ~10Kbp. Because of their ability to move, our genomes are littered with these element to the point where almost half our genomes are just transposons. Compare that to exons making up just ~1% of the genome.

Transposons are classified as Type/Class I (or a better name is retrotransposons) or Type/Class II (DNA transposons). A retrotransposon requires an RNA intermediate which is reverse-transcribed and integrated into the genome. This is a copy-and-paste mechanism. A transposon, on the other hand, is cut-and-pasted into a different location in the genome. Within these two classes too, there are subclasses and so on, and there are efforts to catalog these elements.

Mobile genetic elements are present in virtually all eukaryotes. More here [Wells and Feschotte, 2020].

They are also found in prokaryotes. In the case of bacteria, where it is easier to transfer DNA horizontally between two living bacterial cells (as opposed to vertically between parent and offspring), mobile genetic elements are blamed for carrying around anti-biotic resistance gene as their cargo, making the crisis of antibiotic resistance worse. More here [Partridge et al., 2018].

What else is in there?#

If you look at the genome browser snapshot closely, towards the bottom it says that there are 655 tracks turned off. Why don’t you go explore?

References#

Seth W Cheetham, Geoffrey J Faulkner, and Marcel E Dinger. Overcoming challenges and dogmas to understand the functions of pseudogenes. Nat. Rev. Genet., 21(3):191–201, March 2020.

S R Eddy. Non-coding RNA genes and the modern RNA world. Nat. Rev. Genet., 2(12):919–929, December 2001.

Sergey Nurk, Sergey Koren, and et al. Rhie, Arang. The complete sequence of a human genome. Science, 376(6588):44–53, April 2022.

Sally R Partridge, Stephen M Kwong, Neville Firth, and Slade O Jensen. Mobile genetic elements associated with antimicrobial resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev., October 2018.

Jonathan N Wells and Cédric Feschotte. A field guide to eukaryotic transposable elements. Annu. Rev. Genet., 54(1):539–561, November 2020.